Let me apologize, folks. The Infinite Mystery of God’s existence has caused everyone no end of bafflement and trouble for the past 3,800 years, and although I discovered the definitive answer some time ago, I haven’t actually done anything with it, apart from jotting it down as a to-do item in my Palm. That was pure carelessness on my part.

In any event, yes, God does indeed exist, for better or for worse. If you’re unwilling to just take my word for it, consider this: in all of world literature, only two years are also titles of classic novels: 1984 and 2001. And Steve Jobs chose both of those years for Apple to roll out new operating systems designed to blast apart the existing hegemony.

Of course, we shouldn’t take mere coincidence as the sole proof of a Divine Being’s existence. But it does represent precisely the sort of cheap irony you’d expect God to go for. God created the coconut, which provides vital nourishment, fiber, and drinking water, and He included utensils with it (just break off a piece!) so that humanity could readily access and enjoy it all. And then He stuck it 50 feet above our reach in a tree with no branches.

Odyssey (OCN) is a cryptocurrency and operates on the Ethereum platform. Odyssey has a current supply of 10,000,000,000 with 8,000,000,000 in circulation. The last known price of Odyssey is 0.00215596 USD and is down -4.00 over the last 24 hours. It is currently trading on 14 active market (s) with $4,872,799.52 traded over the last 24 hours. Exodus and Mist are desktop wallets which work as Odyssey, compatible with Windows, Linux and Mac. Jaxx is a versatile wallet, compatible with Windows, Mac and Linux desktops, iOS and Android smartphones, and Chrome and Firefox web extensions. MyEtherWallet is its most popular Web wallet, and ETHAdress is one of the paper wallets.

Similarly, He chose to have Chairman Steve make his first play during the year in which George Orwell predicted we would be struggling against a totalitarian dictatorship. And now, during the year in which Arthur C. Clarke predicted we would transcend our clumsy human forms and move to the next stage of cosmic enlightenment, Chairman Steve is back for a second act.

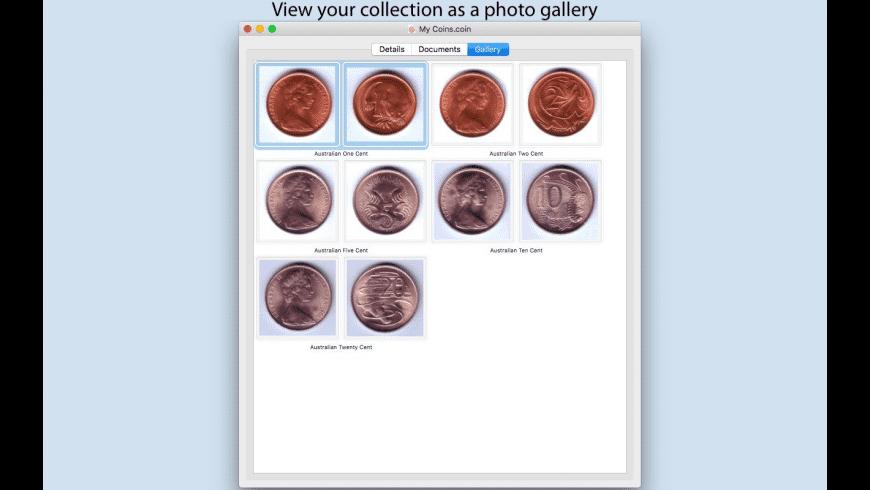

Coin Odyssey Mac Os X

(The Infinite Mystery of why Steve Jobs continues to wear those black mock turtlenecks at important functions remains for the next generation of theologians to ponder, however.)

Thus Spake Jobs

Like it or not, Mac OS X is meant to have the same effect on us as Macintosh System 1.0 had on the MS-DOS world. This time, we are the enemy-and sure enough, Mac users’ grumblings began with Apple’s very first, very cautious demonstration of the Aqua interface.

The more I work with OS X, the more my attitudes and opinions-about almost every aspect of it-flip-flop. I mean, I generally like the Aqua interface, but I worry that Apple has traded elegance for flash. I like the new browser-based Finder, but dangit, it takes up a lot of room on my screen.

And while some people’s first experience with Mac OS X was loading up Microsoft Internet Explorer, mine was compiling GNU source code and excitedly seeing how much I could exploit Mac OS X’s Unix heritage. I’m as captivated by X’s Unix underpinnings as an Adam Sandler fan is by shiny objects. And yet . . . several times in the course of the past year, I’ve skidded around a corner in Mac OS X and found myself transported to the dark, humid realms of lowercase backslash directories when I wasn’t expecting it. It’s dampened my enthusiasm for X every single time. Um, this is still Mac OS, right?

All of this is hot stuff. I can get a lot of cocktail-party conversation out of those comments. But (and I offer this only as a remote possibility) could I be, simply, full of it? Am I evaluating Mac OS X as a brand-new operating system? Or am I just rebelling against having to rethink my 15-year-old definition of the Macintosh experience, as Mac OS X’s architects have done?

Everyone’s going through the same ordeal. It’s delightful and thrilling and frightening. All around me, folks are running around, looting stores, and proclaiming that the End of the Mac is nigh while helping themselves to a couple of DVD players at Best Buy. Others, thoroughly hypnotized by those pulsating buttons, have embraced Mac OS X and are making it do wonderful things that Macs can otherwise manage only in cartoons.

Knee-Jerk Rebels

When we were teenagers, we rebelled against anything and everything that registered on our radar. As we made our way into adulthood, we exploited our rebellious impulses a little more efficiently, focusing them on the issues we deemed truly important.

Eventually, though, we’ve all got to realize that the things it’s most important to rebel against are our own hard-won principles and preconceptions-to realize that sometimes there’s a difference between the Right Way and what we’ve merely come to think of as the Right Way. Our gut-level distaste for something new is less about our reaction to the thing in question than it is about our fears of abandoning the familiar and comfortable.

The computer world faced that challenge in 1984. Some of us were apoplectic with joy about the first Mac and embraced it right away, even though in many ways it was about as useful as a camel that could yodel Gershwin. Others fell in love but managed to restrain themselves until the Mac became a more practical alternative to the status quo. Still others remain unmoved.

2001 will go down as the Proving Year for Mac OS X. People will buy software for it. Apple will release updates for it. Surely, like the original Mac, Mac OS X won’t be truly finished until it arrives at its equivalent of System 4.0. Until then, we won’t know whether that ending will be like 1984 ‘s, in which our impotence against the will of the collective is proved, or like 2001 ‘s, in which humankind gains the ability to play among the stars.

Regardless of the outcome, 2001 will be remembered as the year in which the Mac community irrevocably grew up. And you’ll see how 2001 won’t be like “1984”: This time, the blond woman in running shorts isn’t hurling a hammer at a video image of Big Brother-she’s throwing it at a mirror.

ANDY IHNATKO has written for the Chicago Sun-Times, Playboy, and other publications.

Back when Ars Senior Products Editor Andrew Cunningham was forced to work in Mac OS 9 by his colleagues in September 2014, he quickly hit a productivity wall. He couldn't log in to his Ars e-mail or do much of anything online, which meant—as someone who writes about new technology for an online-only publication—he couldn't do his work. All Cunningham could do was play old games and marvel at the difference 15 years makes in operating system design.

But as hard as it may be to believe in light of yet another OS X macOS update, there are some who still use Apple's long-abandoned system. OS 9 diehards may hold on due to one important task they just can't replicate on a newer computer, or perhaps they simply prefer it as a daily driver. It only takes a quick trip to the world of subreddits and Facebook groups to verify these users exist.

Certain that they can't all be maniacs, I went searching for these people. I trawled forums and asked around, and I even spent more time with my own classic Macs. And to my surprise, I found that most of the people who cling staunchly to Mac OS 9 (or earlier) as a key component of their daily—or at least regular—workflow actually have good reason for doing so.

Why? Whhhhyyyyyy???

The reasons some Mac lovers stick with OS 9 are practically as numerous as Apple operating systems themselves. There are some OS 9 subscribers who hold out for cost reasons. Computers are prohibitively expensive where they live, and these people would also need to spend thousands on new software licenses and updated hardware (on top of the cost of a new Mac). But many more speak of a genuine preference for OS 9. These users stick around purely because they can and because they think classic Mac OS offers a more pleasant experience than OS X. Creatives in particular speak about some of OS 9's biggest technical shortcomings in favorable terms. They aren't in love with the way one app crashing would bring down an entire system, but rather the design elements that can unfortunately lead to that scenario often better suit creative work.

AdvertisementI'm alluding here specifically to the way OS 9 handles multitasking. Starting at System 5, classic Mac OS used cooperative multitasking, which differs from the preemptive multitasking of modern Windows and OS X and Linux. With classic Mac OS multitasking, when you want to change apps it's up to the active program to relinquish control. This focuses the CPU on just one or two things, which means it's terrible for today's typical litany of active processes. As I write this sentence I have 16 apps open on my iMac, some of which are running multiple processes and threads, and that's in addition to background syncing on four cloud services.

By only allowing a couple of active programs, classic Mac OS streamlines your workflow to closer resemble the way people think (until endless notifications and frequent app switching cause our brains to rewire). In this sense, OS 9 is a kind of middle ground between modern distraction-heavy computing and going analog with pen and paper or typewriter.

These justifications represent just a few large Mac OS 9 user archetypes. What follows is the testimony of several classic Mac holdouts on how and why they—along with hundreds, perhaps thousands of people around the world—continue to burn the candle for the classic Macintosh operating system. And given some of the community-led developments this devotion has inspired, OS 9 might just tempt a few more would-be users back from the future.

Coin Odyssey Mac Os Download

Programmatic hangers-on

Remembering how the comments on Cunningham's article were littered with stories of people who still make (or made, until only a short time beforehand) regular use of OS 9 for getting things done, I first posed the question on the Ars forums. Who regularly uses Mac OS 9 or earlier for work purposes? Reader Kefkafloyd said it's been rare among his customers over the past several years, but a few of them keep an OS 9 machine around because they need it for various bits of aging prepress software. Old versions of the better-known programs of this sort—Quark, PageMaker, FrameMaker—usually run in OS X's Classic mode (which itself was removed after 10.4 Tiger), though, so that slims down the pack of OS 9 holdouts in the publishing business even further.

Wudbaer's story of his workplace's dedication to an even older Mac OS version suggests there could be more classic Mac holdouts around the world than even the OS 9ers. These users are incentivized to stick with a preferred OS as long as possible so they can use an obscure but expensive program that's useful enough (to them) to justify the effort. In Wudbaer's case, it's the very specific needs of custom DNA synthesis standing in the way of an upgrade.

AdvertisementCoin Odyssey Mac Os Catalina

'The geniuses who wrote the software we have to use to interface the machines with our lab management software used a network library that only supports 16-bit machines,' he wrote. This means Wudbaer and colleagues need to control certain DNA synthesizers in the lab with a 68k Mac via the 30-year-old LocalTalk technology. The last 68k Macintosh models, the Performa 580CD and the PowerBook 190, were introduced in mid-1995. (They ran System 7.5.)

Coin Odyssey Mac Os 11

This DNA synthesis lab has two LC III Macs and one Quadra 950 running continuously—24 hours a day, seven days a week—plus lots of spare parts and a few standby machines that are ready to go as and when needed. The synthesizers cost around 30,000-40,000 Euros each back in 2002 (equivalent to roughly $35-50k in 2015 terms), so they want to get their money's worth. The lab also has newer DNA synthesizers that interface with newer computers and can chemically generate many more oligonucleotides (short synthetic DNA molecules) at once. This higher throughput comes with a tradeoff, however. Whereas the old synthesizers can synthesize oligonucleotides independently of each other (thereby allowing easy modifications and additional couplings), the new ones do them all in one bulk parallel process, meaning the extra stuff has to wait until afterward. More work means more time, and as Wudbaer says, 'time is money.'

On the Facebook group Mac OS 9 - it's still alive!, people trade more of these OS 9 endurance stories. Some prefer it for writing environment. Others keep it around for bits and pieces of work that require expensive software such as Adobe's creative suite or a CAD package or Pro Tools or specifically to open old files created with this software. Most use it for old Mac games, of which there are far more than the Mac's game-shy reputation would suggest—but that's a story for another day. A scant, brave few not only struggle through OS 9 for these sorts of offline tasks, but they also rely on it as a Web browsing platform.